19th century funfairs were « effervescent laboratories » where entertainment met discoveries. Despite what you might think, showmen played a leading, active and modernistic role in popularising science and technics to the masses.

On the verge of the 19th century, the fair was both entertaining with its colourful and animated images, dioramas, sideshows, and phenomena and commercial.

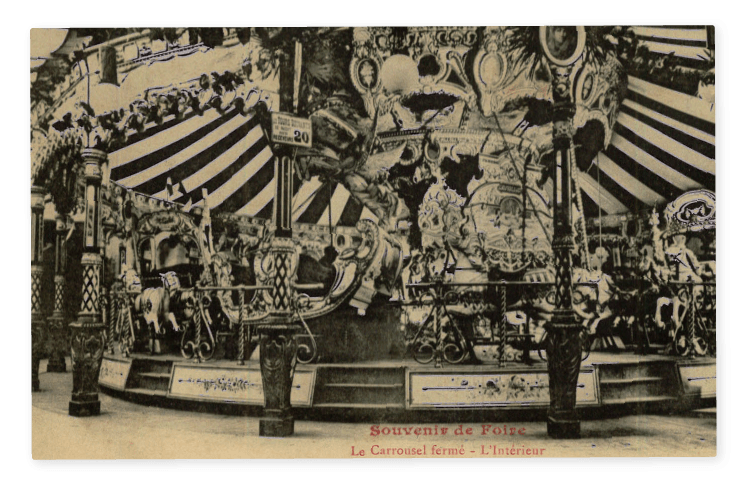

Throughout the 19th century the trade show grew to offer new fairground attractions every year: Velocipede carousels, steam-powered merry-go-rounds, caterpillar rides, haunted houses, train rides and rally tracks.

At the Belle Epoque, fairgrounds were like a condensed version of the world. The masses, made up of the less fortunate and less educated part of the population, gathered to discover the latest scientific wonders. Science was displayed everywhere: on posters for “Cabinets of curiosities, behind the glass cabinets of anatomical wax museums, on painted panoramas and across the showfronts of mechanical theatres.

Fairground amusements from the 19th and beginning of the 20th century combined entertainment with education through the use of modern technology. They offered showy and spectacular insights to mathematics, natural science and human sciences.

In the field of mathematics, the probability theory only appeared at the beginning of the 18th century through the works of Montmort (1708), Bernouilli (1713) and De Moivre (The Doctrine of chances, 1718).

Probability became an autonomous branch of mathematic studies, and its field of application quickly diversified. It is at this time that theory of insurance, lotteries and gambling also appeared.

Although their approach was certainly not highly rigorous and mathematical, showmen used the probability theory to create and present their lottery games. They arranged their lottery wheels in a specific order to modify the chances of winning of the players so that they could increase their profits.

Throughout the 19th century, these street science scholars in physics, chemistry and astronomy turned the roads into science classrooms. They displayed amusing experiments that drove the public into indescribable delights. On fairgrounds, these physics-demonstrators, scientific-illusionists and engineer-mechanics, called themselves Professors. They presented all the modern applications of sciences, especially those that had almost magical effects: electricity, magnetism, optical science, properties of air, and invisible inks.

Sometimes, fairs were at the origin of science progress, as exemplified with the invention of the telescope. In 1608, in Middleburg, Netherlands, Haus Lipperwey, a Dutch showman presented the crowd with a new magical object: an optical device, with two lenses end-to-end that distorted reality and created bewitching effects. According to the legend, Galileo, seized the misleading object from his fellow scientist, and transformed it into a scientific observation device – the first refracting telescope – to prove him wrong.

In the fields of zoology and botany, the fairground displays and representations of animals and plants were focused on showing rather than explaining, but they still introduced the masses to exotic flora and fauna (lions, elephants…). Fairground zoos spread in the 19th century, followed by the funfair tradition of bear tamers that later appeared at world fairs and colonial exhibitions. The fairs offered living models to painters who specialized in animal portraits. This practise also enabled the scholars from the Museum of Natural History and Jardin du Roy to scientifically study the fair’s specimens, allowing, for example, Buffon to study orangutans.

In the field of medicine, the creation of anatomical wax museums in the middle of the 19th century directly correlates with the great medical progress of Louis Pasteur as well as the hygiene-related campaigns. The “professors” of these museums, through their scientific speeches and in newspapers and magazines, claimed that they had an educational purpose. They also preached the benefits of health over the devastating effects of an unbalanced lifestyle.

These museums were divided into various sections such as general anatomy, embryology, obstetric, surgery, phrenology, tetralogy, and anatomic pathologies (the latter presented venereal diseases in a room reserved for adults only). The anatomical wax figures were originally produced by specialized companies for medical studies before being commercialized and used by showmen to satisfy the public’s taste for the monstrous and bizarre. Thus, the Paris school of Medicine’s official sculptor Jules Talrich (1826-1904) created his own anatomical wax museum on the Grands Boulevards and also provided wax figures for others like the Doctor Spitzner’s museum and the Grand Panopticum de l’Univers which operated until 1958.

Healers and tooth pullers also followed the fairs to offer elixirs, balms and ointments with their own secret recipes.

In the field of human sciences, geography was in the spotlight. This infatuation was due to the expansion of colonial empires and the numerous scientific expeditions in the 19th century to explore the earth. Explorers and travelers became the heroes of their time. Their achievements were narrated in all the newspapers, gazettes, and magazines and they inspired many adventure novels. Showmen made the most of this enthusiasm for travel and exploration by recreating landscapes and sceneries of these unknown lands on their fairground attractions.

By the end of the 19th century, funfairs offered patrons the opportunity to voyage all across the world without living their hometown. The visitors were invited on an imaginary journey through animated sets, cycloramas, dioramas and panoramas depicting the North Pole, deserts, jungles, famous cities like Venice, and they got to try rides that displayed some of the newest engineering technology in the world.

By presenting foreign lifestyles that were then considered as “primitive” on fairgrounds, showmen also employed ethnography. Funfairs offered a wide range of representations of foreign civilizations from ethnographic museums that had a certain educational and scientific approach ( including the ethnographic wax figures of Jules Talrich ) to trivial exhibitions that were for entertainment only.

Criminology and crime history – a field somewhere between history and sociology – has always attracted the crowd. People enjoyed seeing crime scenes or witnessing criminals being pilloried. Before the French Revolution, the executioners even took advantages of this morbid interest by exhibiting the bodies in fairground stalls, giving them the idea to turn these temporary “shows” into permanent displays. Therefore, in 1771 the very first permanent wax museum opened in Paris, boulevard du Temple, presenting wax models of popular criminals. Criminality became the main theme of all these bizarre “cabinets of curiosities”.

At the end of the 19th century, these exhibitions joined fairgrounds as traveling museum such as the Grand Panopticum de l’Univers that displayed the wax depictions of the Bonnot gang around 1925.

Showmen not only contributed to the popularization of technical innovations (phonograph, X-rays, hot-air balloons, automobiles, airplanes…) but they also innovated themselves by creating new and unique steam engines, scaffoldings and actuators. Showmen set the safety and reliability standards that were later applied at a large scale within the industry.

This is an excerpt from a pluri-displinary article written by a group of scholars (from L’Université Paris XI – Orsay, le Centre d’ethnologie française, le CNRS-Musée national des arts et traditions populaires et l’Université Denis Diderot)

Authors :

Daniel RAICHVARG, Groupe d’histoire et de diffusion des sciences, Université Paris XI, Orsay — Zeev GOURARIER, Centre d’ethnologie française, CNRS-Musée national des arts et traditions populaires, (MNATP), Paris — Alain MONESTIER, conservateur au MNATP — Jean-Luc VERLEY, professeur de mathématiques, Université Denis Diderot.

Published on 31.03.17